Grateful Dead Studio Albums From Worst to First

2025 marks the sixtieth anniversary of the formation of the Grateful Dead, an American musical institution still thriving all these years later. Dead and Company, featuring original members Bob Weir and Mickey Hart, just finished an extended run at The Sphere in Las Vegas. Bill Kreutzmann, the only other surviving original member, still gigs occasionally in Hawaii (where’s he’s retired) with Billy and the Kids. Boulder has always been Deadhead Central; we may not have the most fans by volume, but we’ve been number one in Deadheads per capita for a long time.

The Dead are marking the feat with Enjoying The Ride, a sixty-CD collection that includes twenty-five shows from some of their favorite venues (including Red Rocks, pictured above). There is also a smaller box set of excerpts, The Music Never Stopped, out in 6LP and 3CD formats. And Dead and Company is playing three sold-out Golden Gate Park concerts in August for (natch) 60,000 fans per night.

So what is it about the Dead that makes them arguably the most successful American musical act of the last sixty years? Few artists have spawned more cover acts or been honored more. Last December the band was recognized at The Kennedy Center Honors, followed in January by a MusiCares tribute over Grammy weekend. Jam bands and non-jam bands cover their material and there have been numerous tribute albums. The stereotypical view of their music may be acid-fueled exploratory jams just as the stereotypical view of their fans may be long hair, but neither fully reflects what’s made the group the leading icons of the sixties counterculture.

When examined en masse, it’s easy to see an obvious thread running through their studio oeuvre: a consistent struggle to translate the group’s concert magic into a representative sound within the confines of a production setting. The Dead’s most unique skill was their ability to form a hive mind through improvisational jamming wherein the different components weaved in and out of each other to create an unique hybrid of jazz and rock. Perhaps it’s not surprising that Grateful Dead studio releases more often than not failed to achieve the liftoff accomplished when the members were clicking onstage.

To help newbies navigate a large and intimidating discography, here are their studio albums ranked from worst to first.

Built to Last (1989)

Built to Last (1989)

In the wake of Jerry Garcia’s near-death in 1986, the Dead experienced a huge boost in popularity, fueled by the huge commercial success of “Touch of Grey.” Suddenly the band filled stadiums with newbies cynically called “Touchheads” by Deadheads. So how did they follow up this long-awaited commercial success? Curiously, by making a record in which they greatly minimized intraband interaction. Built to Last was created largely by having the members exchange parts, each adding their contributions one at a time; maybe they thought this was cutting edge? They also opted to let keyboardist Brent Mydland–who would be dead from a drug overdose within a year–contribute four songs. And while two of those compositions, ”Just a Little Light” and “Blow Away,” are his strongest, the album still bombed. Like their performance at Woodstock, which included an abbreviated “St. Stephen” and a forty-minute “Turn On Your Lovelight,” Built to Last is notable primarily as an example of the group failing to take advantage of a huge opportunity to make an impression.

Go To Heaven (1980)

Go To Heaven (1980)

Go To Heaven features many tracks that became an essential part of the Dead’s eighties musical repertoire. Its horrific cover was inspired (I believe) by a lethal combination of disco, cocaine (the drug of choice at the time) and a failed attempt to be punny. Along with two soft-rock efforts by then-new keyboardist Mydland, the production wrings the life out of every song. “Don’t Ease Me In” dispenses with jamming in the hope of achieving radio play while “Lost Sailor,” a song highly reminiscent of earlier Bob Weir composition “Looks Like Rain,” features a protagonist too easily imagined as one of the group’s more drug-addled fans. But the absolute low point is “Feel Like a Stranger,” an R&B song that sounds like the Average White Band on quaaludes with an abrupt ending that doesn’t come nearly soon enough. How something so good live could be rendered so insipid in the studio is no small achievement.

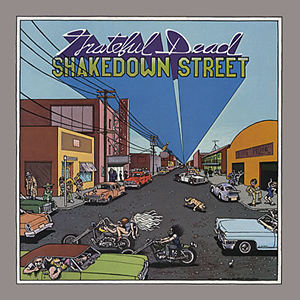

Shakedown Street (1978)

Shakedown Street (1978)

Featuring a classic cover by underground comic artist Gilbert Shelton of Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers fame, the last Dead album of the seventies was produced by Little Feat founder Lowell George. To aid in the continued search for commercial success, George watered down much of the material and substituted polish for heart. Opener “Good Lovin’” abandons the lengthy blues presentation from when Pigpen sang it for a radio-friendly gait closer to The Young Rascals hit (which was itself copied from The Olympics’ arrangement of the original single by Lemme B. Good). “Fire on the Mountain,” which usually lasted ten-plus minutes live, is squeezed into four minutes. The title track might’ve become an anthem in concert, but here it’s sped up in an attempt to capitalize on the disco fad. The remake of “Minglewood Blues” pales next to the high energy of the cover from the group’s debut, and album closer “If I Had the World to Give” is one of Garcia/Hunter’s weaker ballads and was only performed live three times. As is the case with so many Dead studio albums, Shakedown Street casts strong material in a weak light.

Aoxomoxoa (1969)

Aoxomoxoa (1969)

Perhaps no band is more associated with recreational drug use than the Grateful Dead. They got their start as the house band at Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests, and their debut is noticeably influenced by the consumption of speed. Unfortunately, nitrous oxide was the drug of choice for Aoxomoxoa, their third studio effort. The result is a confusing mess that weakens the power of the classic “St. Stephen” and mires “China Cat Sunflower” in a flower-power jumble. “Dupree’s Diamond Blues” marries highly misogynistic lyrics to a calliope effect that sounds like something from a carnival sideshow. But the true nadir has to be the unlistenable “What’s Become of the Baby.” Jerry Garcia and Phil Lesh soon realized the error of their ways, and in 1971 returned to the studio to remix the record and remove a number of its effects.

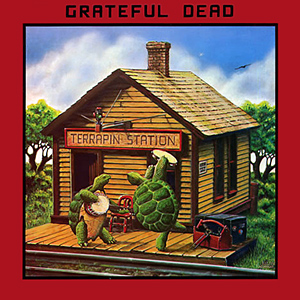

Terrapin Station (1977)

Terrapin Station (1977)

In 1976 famed record honcho Clive Davis signed the Dead to his new label, Arista Records, with the hope of helping them finally achieve mainstream success. To accomplish this goal he paired them with producer Keith Olsen, who had worked with Fleetwood Mac to create the eponymous record that would transform that band’s career. The result is a curious hodgepodge. While it contains some excellent material, most notably the title track and Bob Weir’s “Estimated Prophet,” it is horribly overproduced and applies a studio sheen that runs counter to the group’s spirit. The title track covers all of side two and is an enchanting, multi-part journey with some of lyricist Robert Hunter’s most evocative storytelling, orchestral and choral flourishes and a fiery, percussion-driven jam near its end. At the other extreme, the cover of Motown classic “Dancing in the Street” is simply embarrassing.

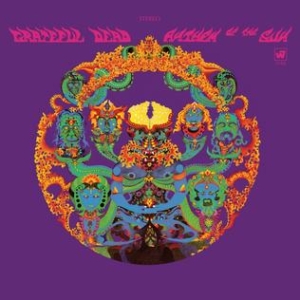

Anthem of the Sun (1968)

Anthem of the Sun (1968)

The Dead’s second album incorporated live recordings and is as psychedelic as they got in the studio. Producer David Hassinger famously exited after being asked to add “thick air” to the sound. After the dizzying speed of the debut, the band leaned into their stage persona and embraced long improvisational sections and Pigpen-led blues rave ups. The record is notable for being the first to entirely feature compositions written by band members. The opener, “That’s It For The Other One,” became one of their most oft-played live numbers in the ensuing decades, although other songs on the record made few if any onstage appearances after 1969. Anthem of the Sun introduced their psychedelic ethos to listeners unfamiliar with the live act and deployed studio effects that made it far ahead of its time. Sections feature multiple live samples interspersed and overlaid in a manner that brings the music in and out of focus much like the acid trips it was performed to.

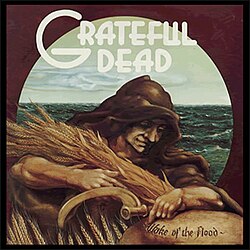

Wake of the Flood (1973)

Wake of the Flood (1973)

The Dead’s sixth studio release was the first on their own record label. In true hippie spirit, the band considered selling it via ice cream trucks as a new, unique distribution method. The songs on Wake of the Flood are uniformly excellent, foundations for long, extended jams that quickly became the highlights of any show in which they were performed. The problem with the studio versions is that the songs are shortened with emotionless vocals and questionable instrumentation. “Eyes of the World” is a shell of the jamming vehicle it evolved into live; “Stella Blue” contains some of Robert Hunter’s most evocative lyrics but includes none of the pathos so endemic to Jerry Garcia’s vocals on his quieter ballads. “Mississippi Half-Step Uptown Toodeloo” adds violin but similarly misses the potential it reached onstage. And Keith Godchaux’s only contribution to a Dead record, “Let Me Sing Your Blues Away,” is a novelty at best.

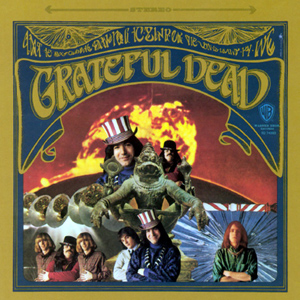

Grateful Dead (1967)

Grateful Dead (1967)

The Dead’s debut is a curious concoction. Recorded in only four days in Los Angeles under the noticeable influence of amphetamines, seven of its nine tracks are covers. The lone group composition, “The Golden Road (to Unlimited Devotion)” is credited to McGannahan Skyjellyfetti, while “Cream Puff War” is Jerry Garcia’s sole attempt at writing lyrics (his partnership with lyricist Robert Hunter began with the group’s sophomore release). Yet the record still has its unique charms. Thanks to all that speed it is furiously upbeat, and even a slow ballad like “Morning Dew” gets played at a faster pace than its live renditions. The album culminates with a ten-minute jam on Noah Lewis’s “Viola Lee Blues,” first performed in 1928 by Cannon’s Jug Stompers, that spirals into the first extended improvisation the Dead committed to vinyl, with Garcia soloing at breakneck speed. Released in March of ‘67, Grateful Dead was the soundtrack to the Summer of Love.

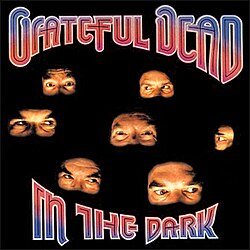

In the Dark (1987)

In the Dark (1987)

In the Dark, released in the wake of Jerry Garcia’s near-death from a diabetic coma in 1986, contained mostly material the group had been playing for years before his illness. But the renewed interest in the group and their biggest/only Top Ten hit, “Touch of Grey,” spurred a popularity that has only increased in the thirty years since Garcia died from a heart attack at fifty-three in 1995. In addition to its lone hit, the record includes two of Bob Weir’s better compositions: “Hell in a Bucket,” a straightforward rocker that opened many shows thereafter, and “Throwing Stones,” as close to a political song as the Dead got outside their cover of Bonnie Dobson’s “Morning Dew,” about the aftermath of a nuclear holocaust.

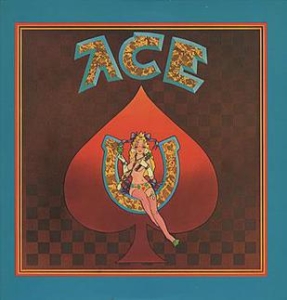

Ace (1972)

Ace (1972)

Ace is billed as a Bob Weir solo record, but his backing band on every track is the Dead, so it merits inclusion on this list (Jerry Garcia’s solo Reflections also features the Dead as backing band on a handful of tracks). Ace is 100% a Grateful Dead record, albeit with strictly Weir compositions. In fact, Ace features the track that sees the group come closest to capturing their live spirit in a studio setting, the nearly eight-minute “Playing in the Band” (the live version on Grateful Dead aka Skull and Roses has no jam at all). The album isn’t perfect thanks to the cheesy mariachi horns of “Mexicali Blues,” but still features some of the best collaborations between Weir and lyricist John Perry Barlow, most notably “Black-Throated Wind” and “Cassidy.” “One More Saturday Night,” the penultimate track, is one of Weir’s few attempts at writing his own lyrics.

Blues for Allah (1975)

Blues for Allah (1975)

Burned out by constant touring, in late 1974 the Dead embarked on a nearly two-year performing hiatus; in 1975 they played only three shows, all in their San Francisco backyard. They returned here with renewed energy. Side one is as good as anything they did in the studio. The trio of “Help on the Way,” “Slipknot” and “Franklin’s Tower” kick things off with a burst of energy, with complex, jazzy jamming and the infectious bounce of the last song in the triad. “The Music Never Stopped” and “Crazy Fingers” similarly match Hunter’s lyrical prowess to strong melodies; the latter is the closest the Dead ever got to reggae. Side two peters out somewhat in a series of more spacey explorations, but not enough to lessen its overall appeal.

From the Mars Hotel (1974)

From the Mars Hotel (1974)

The group’s seventh studio release is the only one that comes close to reaching the heights of the one-two punch of 1970’s Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty. Apart from Bob Weir’s tepid “Money Money,” the album finds the group firing on all cylinders with notable contributions from the songwriting duos of Garcia/Hunter and Lesh/Petersen. The former’s “Scarlet Begonias” became one of the Dead’s most-beloved songs with its romantic lyrics and spirited, open-ended jamming, while the latter’s “Unbroken Chain,” never performed live until shortly before Garcia’s death, marries a hypnotic melody to a complex middle section that hinted at Blues For Allah‘s melodic fusion. Add classics “Ship of Fools,” “U.S. Blues,” “China Doll” and “Loose Lucy”–all songs that elicited strong fan responses in concert–and the result is one of the few studio Dead records that even a non-Deadhead will appreciate.

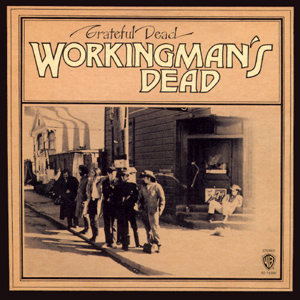

Workingman’s Dead (1970)

Workingman’s Dead (1970)

As the seventies dawned, the folk-rock of Southern California was taking the world by storm. First hatched by The Byrds, The Mamas and The Papas and Buffalo Springfield a few years prior, the genre took a big step forward with the debut release by Crosby, Stills and Nash in 1969. That album’s three-part harmonies greatly influenced the Dead, who did a 180 from the extreme psychedelia of 1969’s Live/Dead, their first live album, and instead opted for shorter, harmony-drenched compositions. Workingman’s Dead surprised fans but also captured a lot of new ones with its anthemic “Uncle John’s Band,” lilting “High Time” and country-tinged “Dire Wolf.” “New Speedway Boogie” speaks to the carnage at Altamont, “Easy Wind,” the only song the Dead did with both music and lyrics by Robert Hunter, features a funky Pigpen lead vocal, and “Casey Jones” closes the album in memorable fashion. The Garcia/Hunter partnership took a giant leap forward here.

American Beauty (1970)

American Beauty (1970)

Workingman’s Dead may have been the album where the Dead took a sharp turn towards folk-rock and CSN-style harmonies, but American Beauty–released less than six months later–is where they reached their studio and songwriting apex. Three of their most widely-known songs–“Sugar Magnolia,” “Ripple” and “Truckin’”–are included. Garcia and Hunter also penned two of their most beautiful, resonant tracks, “Brokedown Palace” and “Attics of My Life,” while Hunter wrote the words for Phil Lesh’s album-opener “Box of Rain” to help the bassist deal with the impending death of his father. Add in the David Grisman-aided “Friend of the Devil” and loping “Candyman” and you have a perfect record without a wasted second. If I was going to try to turn someone on to the Grateful Dead, this is where I’d start.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!